Article: Kantha Stitch

Kantha Stitch

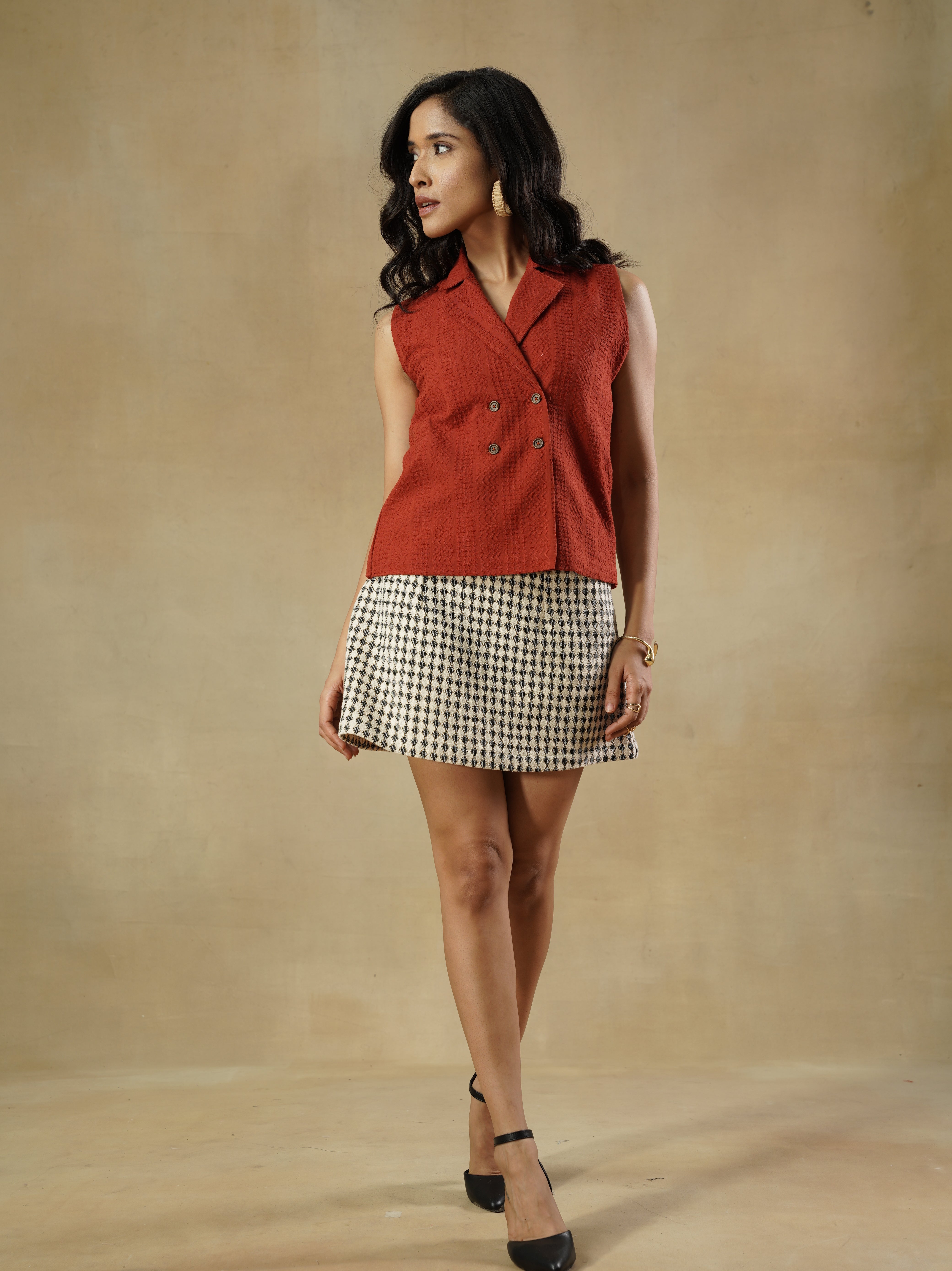

Kantha stitch is one of the techniques that we use in our garments, and this blog would dive into how this stitch came to being, its importance, and what led us to using it. From a stitch rooted in the history of clothing, this stitch has come a long way from its early days. Here’s our take on the infamous kantha stitch.

What is Kantha Stitch, where does it come from?

Kantha stitch is an ancient technique, one of the oldest forms of embroidery that rises from our nation, India. Began in Bengal, this old tradition of stitching patchwork is now very famous in West Bengal, Orrisa and Bangladesh.

Initially this technique was used to repurpose old sarees & fabrics into quilts. This technique involves both styles of running stich and finished cloth. Practiced often by rural women to create different pieces of cloth, this technique was passed down the generations and it lives on even today.

Rooted in culture, this technique, like many others, lives on through the years and breathes through different implemented designs even in the modern-day landscape.

After being born in the rural villages of Bengal, this practice got lost in the early 19th century, only to be revived in the 1940’s by the daughter in law of the Bengali poet, Rabindranath Tagore.

Then again while the partition was taking place, the skill of Kantha stitch got lost in the hustle again. But as the Bangladesh war ended in 1971, the art form saw a revival.

The word Kantha seemingly has been derived from the Sanskrit word “Kontha”, which meant rags. As with all traditional textiles, Kantha too was concerned with other factors such as availability, daily needs, geography, and economic factors. Thus, the recycling of well used cloth-turned-rags was a natural step in the lifecycle of textiles the world over. Given that this recycling was home-based work, it usually fell to the women of the village to prepare, cut and stitch the rags - giving old textiles new life.

About the stitch

The earliest stitch in Kantha was the basic, straight, running stitch which could be seen in many pieces early on, which then evolved into what was later on called as “Nakshi Kantha”. As any art does, even Kantha became more layered, intricate – as time passed by. The term “Nakshi” comes from the Bengali word Naksha which refers to artistic patterns.

What’s great about it is that the shape is formed by looping threads on side of the surface that allows the flip side to have just a plain running stitch whereas the oth er side complex geometric patterns.

If we were to categorise on the basis of the stitch type, there are a few kinds of kantha stitch.

The main types are:

- Running kantha is the earliest kind and the most commonly adopted type of the stitch.

- Lik or Anarasi kantha is practiced in Jessore areas of Nothern Bangladesh.

- Lohori kantha or wave kantha is popular in Bangladesh and is divided into three kinds, namely, kautar khupi, soja and borfi.

- Sujni kantha is often found in Bangladesh but is also practiced in Bihar, and one of the popular motifs is a wavy floral and vine pattern.

- Cross-stitch or carpet kantha was introduced by the British while ruling india.

About the cloth

Traditionally, this stitch was used majorly in Bengal as coverlet during the mild breeze of Bengal during winter time and monsoon. Besides this, many women often used to stitch kantha during their pregnancies to create swaddles and different kinds of cloth, one would be to use it and the second would be in prayers for the health of the new born baby.

Kantha on the traditional cotton fabric was much easier than the silk fabric layers that our kantha artisans create; while cotton layers stick together, silk slides and slips and the kantha is much more time consuming.

For par tola geometric kantha, the stitching count is done from memory; no pattern is drawn. For nakshi kantha, the pattern was traditionally outlined with needle and thread. Today, patterns are first drawn by pencil and then copied by tracing paper onto the fabric. In some types of kanthas (carpet, lik and sujni, etc.) wooden blocks were used to print the outline.

If you travel through Bengal today, you'll still come across modern versions of the traditional patchwork kantha quilts—draped over verandahs in Kolkata to air out in the sun or spread across paddy fields in villages to dry. However, most kantha embroidery today is produced for commercial markets, both within India and Bangladesh and for export. In theory, this shift has created opportunities for rural women who, due to economic, cultural, and social constraints, have limited access to formal employment. The rising demand for kantha has allowed them to work from home and contribute to their households financially.

In reality, though, kantha artisans face the same exploitation that plagues the wider handicraft industry in the region.

A study published in the Journal of Social Work and Social Development revealed that many of these women are underpaid, experience inconsistent or delayed wages, and lack the training or financial support needed to improve their livelihoods. On average, a kantha artisan earns only Rs.2,000–4,000 (USD 30–60) annually—a sum that is nowhere near a sustainable or fair wage, even when considering that most women work part-time.

Fortunately, awareness around ethical production is growing. More designers are recognising the need for fair trade practices, making it possible to find responsibly made kantha textiles—like those crafted at House of Wandering Silk.

2 comments

yj567v

✉ 🔔 Notification: 0.95 BTC ready for transfer. Confirm → https://graph.org/Get-your-BTC-09-04?hs=4154057e4252747d77d55f5c7aa93262& ✉

fbewg0

🔍 Security Alert; 1.05 Bitcoin transfer attempt. Deny? >> https://graph.org/Binance-10-06-3?hs=4154057e4252747d77d55f5c7aa93262& 🔍

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.